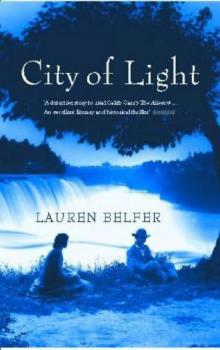

Read City of Light (v5) Storyline:

Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Even the considerable length of Lauren Belfer's City of Light can't prepare the reader for all the novel holds. In turn-of-the-century Buffalo, she illuminates (among other concerns) the struggles of women, blacks, immigrants and lesbians, labor unions and socialists; the birth of environmentalism; the back-room dealings of industrialists; and the illegitimate children of predatory U.S. Presidents. The novel truly contains multitudes, yet it finds its heart in, and its focus through, Louisa Barrett. The headmistress of the Macauley School for Girls, Louisa is "tall, slender, almost-blond, sensitive, and basically shy though sometimes appearing on the surface bossy and a know-it-all." A salon of noted intellectuals convenes at her home, and she enjoys the protection of the powerful men who sit on the school's board. She is considered "one of the boys," yet Louisa merely enjoys proximity to power and must still struggle with the strictures society places on her gender. In hope that there might be a future in which women of equal intellect will enjoy true equality, she exposes her students to all things (e.g. poverty, hydroelectricity) under the cover of producing marriageable young women. One student, Grace Sinclair, occupies her more than the others. She is Louisa's godchild and has been acting strangely, frightening other girls with her morbidity; this in itself is not surprising, as Grace's mother, Margaret, has recently died. Her father, Thomas, attempts to understand his daughter while simultaneously directingthenew hydroelectric project at Niagara Falls. A true believer in industry's possibilities, Thomas is hoping to "change the world with electricity" and is impatient with any resistance to this new source of energy. Electricity is still little understood by Buffalo's society, but expectations run high: "it seemed like magic, but it was science. Magic had become science, science had become magic, anything was possible and the future was ours." At the Sinclairs' home one evening, Louisa overhears Thomas arguing with an engineer, Karl Speyer; when Speyer turns up dead the next morning, Louisa begins to suspect Thomas. His surprise gift of one million dollars to the Macauley School exacerbates her suspicions she wonders if he's trying to buy her silence. The world these characters inhabit is fraught with intrigue, every action fueled by old secrets and whispers, hopes of profit. Louisa seeks the truth, the light that casts the shadows; at the same time, she strives to protect those she loves and to keep her own dark secret hidden. In the world of City of Light , to know someone's secrets is to determine his or her actions. This is a book about control, and about forces that can only be controlled at some cost. Just as men restrain and channel those women who seek knowledge and access to power, they harness the force of Niagara Falls and the labor of the underclass. Belfer's writing is also characterized by control; her narrator, Louisa, is ingeniously selective in how she reveals herself, while at the same time exposing (and drawing the reader into) her own blind spots. The prose is taut and precise, rich but rarely too rich, rife with surprising insights. Here's Louisa, entering a room illuminated by electricity: "the air itself seemed clear, vibrant, and somehow invigorating. All at once I knew why: Gaslight consumed the oxygen in a room; electricity did not." Later, taking leave of a man she fears, she wonders "Could he possibly have formed a romantic attachment to me, or did he simply regret losing the opportunity to torture me? Or were the two the same to him?" Louisa seems to possess a political sensibility of the 1990s, yet she must continually hold herself back. "[I]f I lost my reputation," she reasons, "I would lose everything I had worked for." While the reader chafes along with her, this is not the only frustration that finds its expression in Louisa. Certainly, as its narrator, she is responsible for the novel's greatest delights; however, she must also be held accountable for its often confounding tone. The wealth of historical information sometimes threatens to overwhelm the narrative's dramatic momentum; early on, especially, the novel can feel more like an education than an entertainment. Louisa speaks with great historical precision for pages at a time, invoking names, dates, architects, and other obscure details, and this works against the process of identifying with her, of bringing her into proximity. The return from such encyclopedic flights to more personal dramas is not always an easy one, and occasionally we get stilted sentiment where heat might be desired. The effect on the reader is a strange combination of longing, frustration, and fascination Louisa often calls us closer only to hold us away. It is easy to understand why so many of the novel's characters seek to form attachments with her. City of Light could be a slicker, smoother book, but it would be less of one. The novel's ambition can't be denied and must be acknowledged and appreciated. If the sheer range of all Lauren Belfer attempts to include leads to some awkwardness, it's a small price to pay. Through ingenious storytelling, she does not merely re-create a world, she creates one, and populates it with finely textured characters some historical, some fictional, some a mixture: all real. Just when the plot begins to seem too carefully set up, the characters too choreographed, and the mysteries too perfectly explained, another level of secrets is exposed. This book unfolds. And in the end, the story turns in a way that explains the reason behind its telling, the force behind its shape and tone. The result is a novel that is alive, haunted, and large in every sense of the word.Pages of City of Light (v5) :